The following is from my memoir Someone’s Hero.

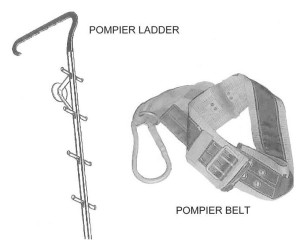

In yet another exercise of how to control fear and develop confidence while using outdated firefighting and rescue equipment, our instructors sent us up to the third floor of the training tower with something called a Pompier ladder. Firefighters are trained to stick a Pompier ladder out of a window, hook it onto the window sill on the floor above, then climb up on the outside of the building or to put it on the window sill on the floor you’re on and climb down to the floors below.

Instead of having sturdy rungs between sturdy beams like a normal ladder, a Pompier ladder is nothing more than a single hollow square beam of metal about ten to twelve feet long with round tubes sticking out of each side for foot and hand holds. At the top of the main beam, is a thin vertical blade of metal with little saw-like teeth cut into it. These teeth are designed to bite into the windowsill it’s placed on. If, God forbid, the teeth lose their bite while you’re on the ladder, there’s a big hook at the end of the vertical blade that’s supposed to stop you and the ladder from plummeting to the ground.

Instead of having sturdy rungs between sturdy beams like a normal ladder, a Pompier ladder is nothing more than a single hollow square beam of metal about ten to twelve feet long with round tubes sticking out of each side for foot and hand holds. At the top of the main beam, is a thin vertical blade of metal with little saw-like teeth cut into it. These teeth are designed to bite into the windowsill it’s placed on. If, God forbid, the teeth lose their bite while you’re on the ladder, there’s a big hook at the end of the vertical blade that’s supposed to stop you and the ladder from plummeting to the ground.

My partner for this exercise was Jim Trewhitt, a life-seasoned firefighter with some grey in the thin black hair that sat high up above his forehead. Glasses with thick black frames always seemed out of place on his face but not the wry smile that accompanied his easy Tennessean style. I, on the other hand, was a 21year old tight-ass with plenty of thick dark brown hair who needed a crowbar to pry my lips into a smile. We were a natural fit.

Jim and I climbed the inside stairs to the open tower’s third level. Standing on the metal grate that served as a floor, I poked my head out of the window (just a rectangular hole framed in cement block with a concrete sill) and studied the pavement below. I figured the height was great enough to break some bones if we fell but unless someone’s neck snapped on impact, it should be survivable.

Jim knew what I was doing.

“I’ll go first,” he said as he checked the snap hook on his Pompier belt. “There’s nothing to it.”

I didn’t find his words all that reassuring but I knew if the old man did it with everybody down below watching, what choice would I have but to do it too.

Jim lowered the ladder out of the window and rested its teeth on the window’s concrete ledge. The top of the ledge was beveled instead of flat and I could see that the actual surface area where the teeth rested was only about ½ inch wide. I steadied the top of the ladder then Jim swung around and stuck his leg out, blindly searching for one of the offset foot pegs down below. After his whole body was outside the tower, he slowly climbed down until both feet were firmly on the bottom pegs. Next, he snapped the big metal hook attached to his leather Pompier belt to the ladder’s main beam. Then, extending both arms straight out from his sides, Jim leaned back into empty space and assumed the “Look ma, no hands!” position for the instructors down below.

Suddenly, the ladder began sliding out the window. All I could do was stare in disbelief as the row of tiny metal teeth skidded across the beveled sill unable to dig into the concrete. Just as it was designed to do, the hook at the end of the vertical blade slammed against the inside of the window ledge and stopped Jim from falling further.

I reached out of the window and steadied the top of the ladder as best as I could.

“Climb back up!” I ordered.

Without looking up at me, Jim cautiously released his hook from the main tube. Then, climbing up one haltering step at a time, he made his way back up and I pulled him back into the tower.

Safely back on the sturdy metal grate, Jim nudged an open pack of Pall Malls from the breast pocket of his sky blue uniform shirt, smacked a cigarette out and stuck it in his mouth. His left hand pushed the pack back into his shirt as his right hand fished a stainless steel Zippo lighter out of his pants pocket. The click of the Zippo opening, the intoxicating smell of naphtha, and the rasp of knurled steel scraping flint, followed by a woomph as bright flying sparks became blue flame tipped in yellow, all reminded me of my dad.

Jim bowed his head and gently introduced the tightly packed tobacco wrapped in virgin white paper to the flame. He inhaled the smoke purposefully, deeply, obtaining great relief. Then he took the cigarette from his mouth and paused to study it before slowly exhaling.

Jim looked over at me with his trademark wry smile.

“Your turn.”

What? I had thought that after Jim’s near-death experience, the instructors would cancel the exercise. But nobody seemed concerned as they all looked up from below, waiting for me to go next. Jim unbuckled his Pompier belt and held it out in front of me like a cowboy offering a bridle to a skittish horse.

“You’ll be fine,” he said with his cigarette bouncing between his lips.

Unlike the exercise days before, when I was on the fire station roof getting ready to jump into a life net, today I had no mental confusion or self-preservation conversation. I had already learned how to put fear and doubt aside when I had to. So I put the safety belt on, cinched it up, took a final look at Jim, then slid out of the window.

When I finally felt my foot step on the ladder’s bottom peg suspended in midair, I hooked in then slowly brought each arm straight out to each side. Even more slowly, I leaned back into space. I held that vulnerable pose and looked up to see Jim’s face above me smiling down with approval.

I developed a special bond with a handful of people during my three decades in the fire service and Jim Trewhitt was the first.

I developed a special bond with a handful of people during my three decades in the fire service and Jim Trewhitt was the first.